This blog post is a joint effort between Praescient Analytics and one of our premier technology partners, Recorded Future.

In a previous post, we discussed how advanced open source collection and analysis tools can be used to explore the resonance of protests in open source media. Digging a little deeper, using Recorded Future’s cutting edge capabilities, we can identify the root causes for labor unrest in Southeast Asia and identify implications for the future of the global garment industry.

Regional Context

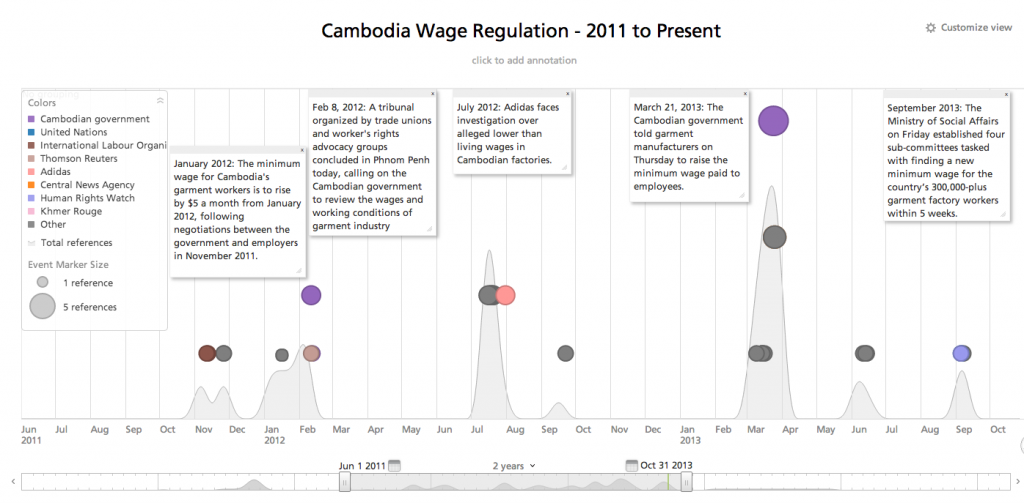

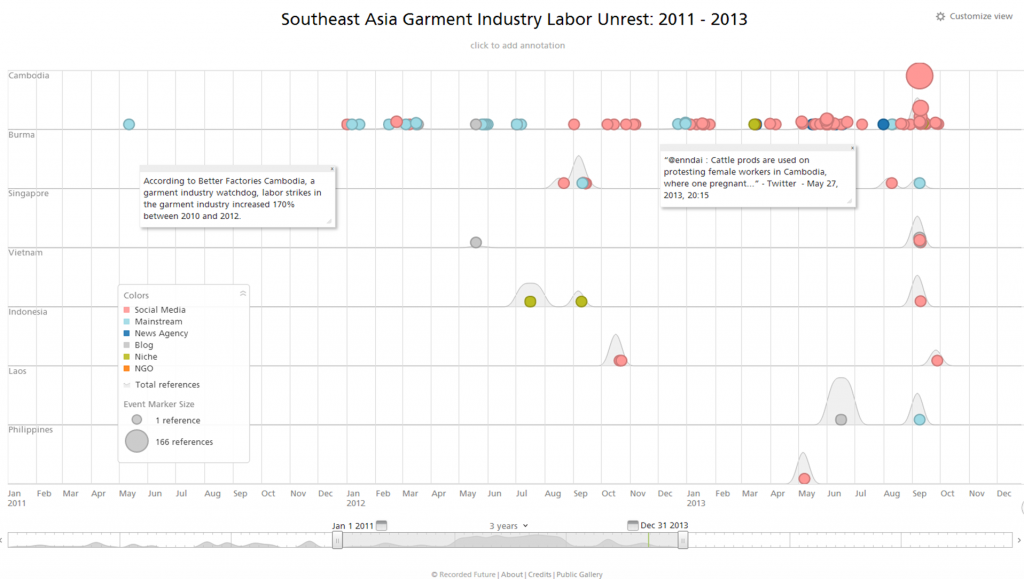

A review of open source reporting for the past two years reveals numerous instances of labor unrest—particularly protests—throughout Southeast Asia. It is immediately apparent that Cambodia experienced the greatest number of labor unrest events throughout this period. Most recently, a group of 4,000 Cambodian garment workers protested the sacking of hundreds of their fellow coworkers who participated in protests over working conditions in Cambodian factories.1

This graphic depicts instances of unrest or labor issues related to the garment industry in Southeast Asia. Click for an expanded view.

According to Better Factories Cambodia (BFC), a nonprofit organization that monitors the garment industry in Cambodia, the number of factories producing clothing for export has increased to 412 as of April, an 8% jump over the preceding six months. At the same time, between 2010 and 2012, the number of strikes jumped 170%. The group points to a number of factors influencing labor unrest, ranging from working conditions to wage compensation.2

Wages as a Key Protest Driver

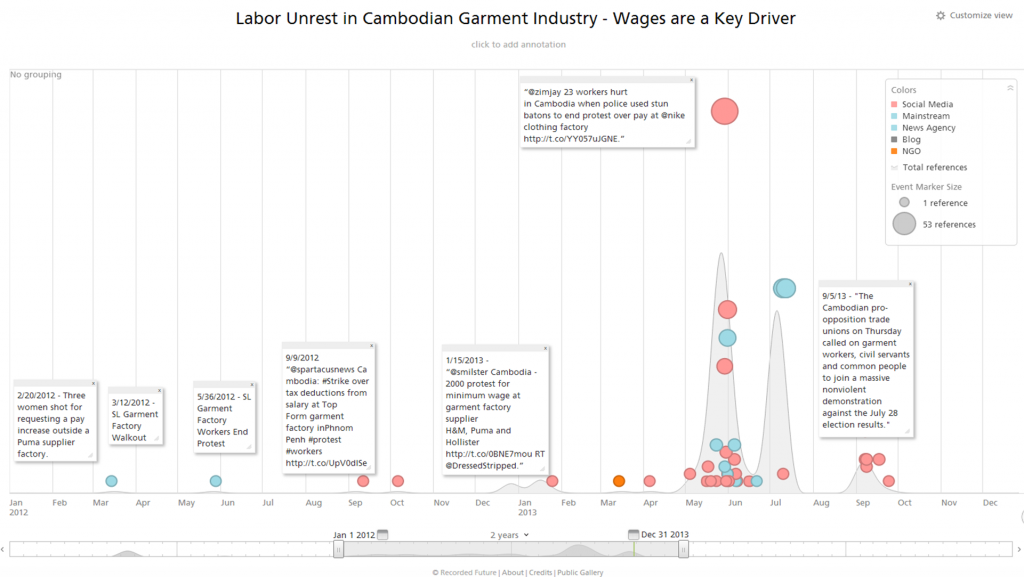

This confluence of two factors—namely, a rapid increase in clothing production facilities to satisfy the export market and the exponential growth of labor protest events—deserves further investigation. Recorded Future allows us to identify and analyze open source references to labor unrest related to wage issues, and visualize the results temporally. Upon review of the data, it is clear that open source reporting confirms the conclusions reached by BFC—that wage-related conflicts are a significant point of contention between factory owners and workers.

This graphic demonstrates that concerns surrounding low wages have been a driving force for protests in Cambodia. Click to expand.

(Click here for an interactive version of this graphic)

Fortunately, this trend is not lost on the Cambodian government. Throughout the past two years, progress has been made to address the wage-related concerns of the country’s 300,000-plus garment industry workers. In January 2012, the minimum wage for garment workers increased following negotiations between the government and industry employers. Throughout 2013, the Cambodia government has continued its push for increased wages for workers in the garment industry. Most recently, in early September 2013, the Cambodian Ministry of Social Affairs established four subcommittees to establish a new, higher, minimum wage standard for the industry.

International Monitors

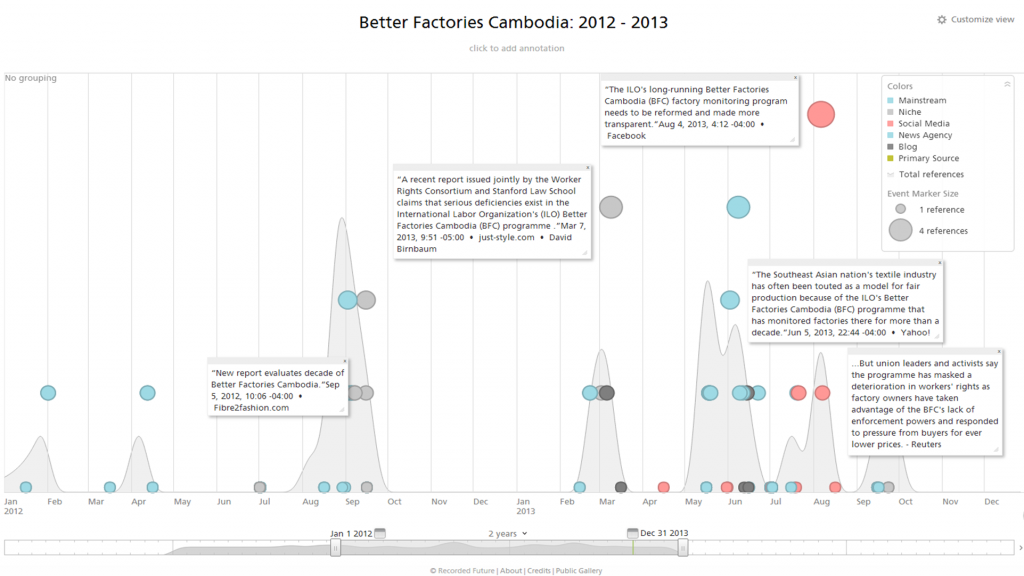

While low wages are a key factor driving protests, other concerns including hazardous working conditions and crackdowns against organized labor also shape the decision of workers to strike. Internationally recognized monitoring organizations like BFC exist to provide oversight and accountability for the industry. In a July report, BFC noted that deteriorating factory conditions are likely a result of recent industry growth.3

Despite the positive role BFC is playing in its effort to hold individual factories and the greater garment industry accountable, concerns have emerged about the effectiveness of their monitoring efforts. A recent article by the New York Times highlights the fundamental challenges that all monitoring organizations face in seeking accurate monitoring through factory inspections:

“…factory managers have been known to try to trick or cheat the auditors. Bribery offers are not unheard-of. Often notified beforehand about an inspector’s visit, factory managers will unlock fire exit doors, unblock cluttered stairwells or tell underage child laborers not to show up at work that week.”4

For its own part, BFC received heightened scrutiny when a Stanford Law School report emerged in February 2013 alleging declining working conditions and wages in Cambodia. This commentary ran in stark contrast to BFC’s narrative, which painted Cambodia as the success story of Southeast Asian garment manufacturing.5

This graphic, depicts recent media references to BFC. Of note, the spikes in reference counts surrounding the release of the Stanford report in February. Click for a larger view.

International Linkages

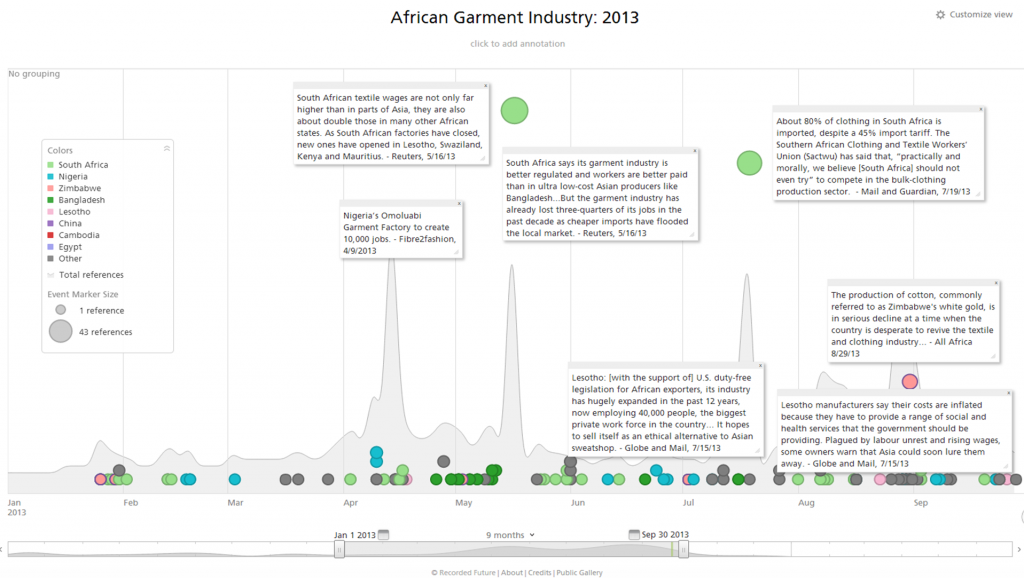

Cambodia has garnered a great deal of media attention in the last few years, both for its growth as an export clothing manufacturer and its accompanying rise in labor unrest. It is reasonable to conclude that other countries around the world might face similar challenges as factory owners struggle to meet rising global demand for inexpensive consumer goods. To dig a little deeper here, we asked: to what extent is labor unrest pushing corporations to seek out suppliers in other markets in emerging markets, such as Africa? Using Recorded Future, we structured a query looking for instances of garment industry growth—or decline—in several key African countries (Lesotho, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe).

This graphic depicts our results, indicating mixed results in the countries searched. Click for an expanded image.

While there is evidence to suggest that working conditions in some African clothing factories may be better than their counterparts in Southeast Asia, open source reporting indicates a number of challenges exist as well. In South Africa, for example, higher wages and better working conditions have raised costs, leading clothing factories to move their operations to other locations across the continent.6 Separately, Lesotho has experienced growth in its garment sector, according to media reports; however, manufactures face increased costs as business owners providing basic social and health services to employees. Sources also indicate that labor unrest has become a worrying factor.7

Future Implications of Open Source Analysis

Open source analysis can help organizations grasp a better understanding of the global labor environment and operational opportunities and risks. Through this brief analysis we identified critical trends using Recorded Future that describe some of the root causes for labor unrest in Southeast Asia. Empowered with these insights, business owners will be better positioned to develop practices that seek to ameliorate tension in their workforce, minimize labor disruptions, and increase productivity. With a better grasp for the root causes of unrest, and the industry’s response to its workforce, governments can develop smarter policies that improve working conditions while maintaining Cambodia’s competitive edge within the global garment marketplace.

Sources

- “Cambodian garment workers protest over alleged mass dismissal,” Agence France Presse via Channel News Asia, 05 September 2013.

- “Thirtieth Synthesis Report on Working Conditions in Cambodia’s Garment Sector,” Better Factories Cambodia, 18 July 2013.

- Ibid.

- “Fast and Flawed Inspections of Factories Abroad,” New York Times, 1 September 2013.

- “Monitoring in the Dark: An evaluation of the International Labour Organization’s Better Factories Cambodia monitoring and reporting program,” Stanford Law School and Worker Rights Consortium, February 2013.

- The cost of no sweatshops: South Africa struggles not to be Bangladesh,” Reuters via The Star Online, 16 May 2013.

- 800 jobs on the line as firm fights crunch,” Lesotho Times,22 August 2013